Community Colleges as Anchor Institutions in Rural Areas

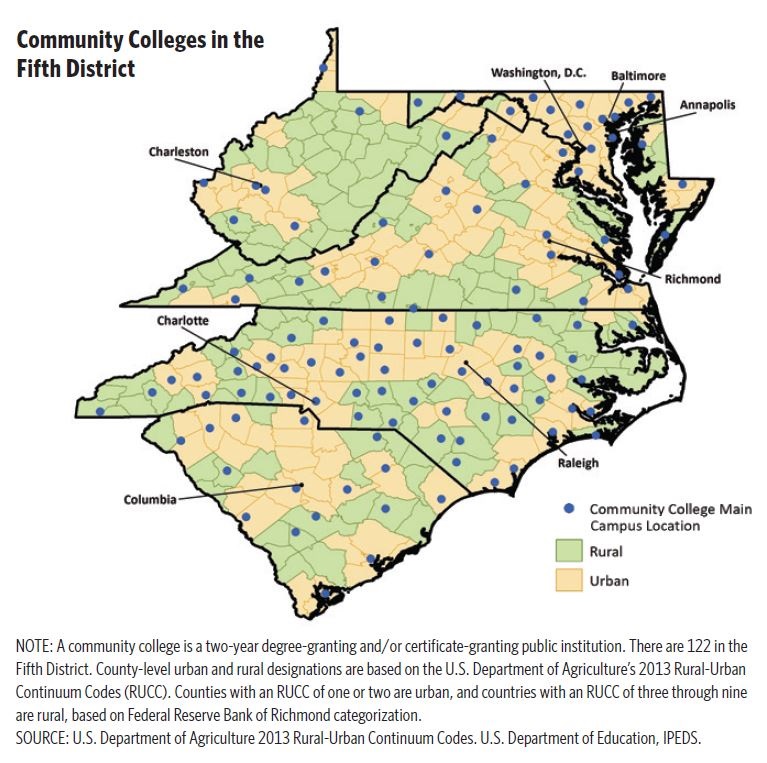

The Fifth Federal Reserve District — comprising Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, most of West Virginia, and Washington, D.C. — is home to 122 public two-year institutions that have a wide range of both traditional academic and technical programs. More than half of these community colleges are located in rural counties. The 66 rural community colleges, like the private and public four-year institutions of higher education in rural areas, play an anchor institution role in their communities. But this role is not always accounted for in the formulas that federal, state, and local governments use to fund institutions of higher education. Understanding and appropriately measuring the role that community colleges play in rural areas is important to how we evaluate policies and funding for workforce and community development throughout the rural Fifth District.

The Anchor Role of Community Colleges

Community colleges, sometimes known as junior or technical colleges, are institutions of higher education that play an important role in the landscape of workforce development, particularly for traditionally underserved populations. Community colleges offer two-year curricula for associate degrees; provide transfer programs to four-year degree programs; offer short-term certificate and credential programs; identify and provide training required by local employers; and augment local high school course offerings. (See "Community Colleges in the Fifth District: Who Attends, Who Pays?" Econ Focus, Fourth Quarter 2019.) Their role in education and training is well known, even if there is work to be done in measuring their success in that area.

What is less well known is their role beyond education and workforce development, particularly in rural areas. In many rural regions, the community college may be one of the few institutions with the local presence and trust to facilitate economic and community development — in other words, community colleges play the role of anchor institution. Anchor institutions are organizations that have influence, trust, and a role in their communities beyond their immediate (usually public) mission. In addition, according to the Rural Local Initiatives Support Corporation (Rural LISC), "anchors can hire employees from the local community, buy needed goods and services from local small businesses, and develop and preserve real estate in their surrounding neighborhood to create places for local residents and employees to live and shop." In small towns and rural areas with few large employers, these anchor institutions often remain stable drivers of economic activity.

Research on anchor institutions often centers on large universities and hospital systems — the so-called "eds and meds" — and their role in community and economic development. (See "Rural Hospital Closures and the Fifth District," Econ Focus, First Quarter 2019.) The Alliance for Research on Regional Colleges underscores the importance of rural public colleges, including community colleges, in sustaining local economies and fueling economic development — including not only providing college-educated workers for local industries, but also building infrastructure or building trust in the community. For community colleges, this community role can be even more central because they often serve a formally defined area, such as a set of counties.

Rural Community Colleges in the Fifth District

The 122 community colleges in the Fifth Federal Reserve District are not distributed evenly among communities. North Carolina, for example, aims to have a community college within a 30-minute drive of any citizen of the state. With its 58 community colleges, North Carolina has the third-largest number of community colleges in the country. Additionally, it has the fifth-largest number of students enrolled in community colleges, while ranking ninth in terms of overall population. West Virginia, on the other hand, has only nine community colleges; of course, West Virginia also has a smaller population. Nonetheless, on a per-capita basis, North Carolina has the largest community college system in the district.

Given that population is not distributed evenly across places, it is not surprising that community colleges are not distributed evenly within district states. In Virginia, for example, the largest community college (Northern Virginia Community College) and the highest concentration of satellite campuses are in Northern Virginia, which is also home to over a third of the state's population and employment. These more populated areas also have more options for higher education in general, via four-year public institutions or private colleges and universities. On the other hand, in the more rural parts of Virginia, the local community college is often either the closest or the only source of higher education or postsecondary skill development for area residents.

Community colleges in rural areas can also be one of the largest employers in the region. Craven Community College in Craven County, N.C., for example, employs 331 full-time equivalent (FTE) people in a county with a population of 101,000. That creates a presence in their region that Central Piedmont Community College in Charlotte, which employs 1,516 (FTE) in a county of 1.1 million, does not. In fact, rural community colleges are frequently among the top 10 employers in the county where their primary campus is located.

Anchoring Initiatives of Community Colleges

Like many anchor institutions, rural community colleges can make investments directly in their communities while leveraging their institutional influence and capacity to build momentum around projects. In rural North Carolina, leaders at Mayland Community College had a vision of turning Mitchell, Avery, and Yancey counties into a regional destination. Thus, they created the Mayland Community College Enterprise Corporation, which has supported downtown development in the town of Spruce Pine; partnered locally to develop an observatory and the largest public telescope in the Southeast; and driven the redevelopment of a hotel and downtown event space. There are other examples, too: Eastern West Virginia Community and Technical College and North Carolina's Piedmont Community College are leading efforts to drive innovation in their local agriculture industries.

Community colleges often serve as resource hubs in rural areas with limited access to important institutions and as providers of critical services. The Technical College of the Lowcountry in South Carolina provides support services to local businesses and community members. For example, its Hampton Campus, in rural Hampton County, S.C., has a public computer lab that anyone in the community can access; for some, it's the only local access to computers and, particularly, reliable high-speed internet. The college also operates the Center for Business and Workforce, which provides free seminars and tutorials to local small business owners. Lack of child care, a frequently cited barrier to employment, presents a challenge in rural areas. In South Carolina, Northeastern Technical College partnered with the Chesterfield County First Steps to start an on-campus child care program to serve students and working parents in the community. The child care center of Vance-Granville Community College in North Carolina is another example. This facility is used as a training laboratory for students, but also serves the rural community with a high-quality child care option for local residents. Chesapeake College in Maryland operates a facility called Corner of Care, which provides toiletries, food, and beverages for those in need.

A direct way that rural community colleges contribute to economic development is by partnering with businesses and leveraging their strengths in workforce development. Local businesses seeking to shore up their workforce with specific skills may look to a rural community college. In order to invest in local workers, Danville Community College in southside Virginia partnered with Hitachi to design a curriculum around the types of skills Hitachi needed in its workforce. Community colleges can also attract businesses and industries to rural areas with tailored training and education programs. The readySC program guarantees customized training and recruiting systems for companies that bring new jobs to the state via relocation or company expansion. Rural South Carolina community colleges, such as Orangeburg-Calhoun Technical College, provide readySC programs for companies in their service area along with corporate training courses that can be utilized by any local company or institution.

Funding Community Colleges

While community colleges, especially in rural areas, play a role that goes beyond educating their enrolled students, the funding mechanisms that support the schools are largely based on enrollment.

Revenue streams for community colleges can vary by college, location, and program, but most community colleges in the Fifth District are funded primarily through a combination of tuition and state government funding. In Maryland, North Carolina, and South Carolina, local funding is also common, while it is much rarer in Virginia and West Virginia. In some cases, the economic or community development activities of colleges are funded through other sources, such as external grants.

Most of the time, state funding is tied to enrollment. In Virginia, for example, state appropriation bills from the General Assembly allocate general funding to the Virginia Community College System, which then allocates it to community colleges based on enrollment (funding can also be designated for specific programs at specific colleges). North Carolina provides community colleges with a base amount of support regardless of size (15 percent of funding) but then allocates funding primarily based on enrollment (83 percent of funding) and to a small extent based on student outcomes across a standard set of measures (2 percent of funding). Maryland has an allocation mechanism that is heavily based on enrollment. West Virginia recently passed a new performance-based funding formula that relies on enrollment for base funding; it will go into effect in 2024. South Carolina also has a funding formula that is based on enrollment (although it is used in a less formal way than in other states).

"Increasing Rural Capacity: Ways Intermediaries Can Contribute," Regional Matters, March 17, 2022.

"A New Approach to Measuring Community College Outcomes," Speaking of the Economy, June 8, 2022.

"Community College as a Steppingstone," Economic Brief No. 22-50, December 2022.

There are also federal and state supports targeted specifically to students for use in higher education. For example, many low-income community college students use federally provided Pell Grants if they are seeking traditional associate degrees or for-credit certificates. Pell Grant funds make up a significant percentage of community college revenues; this is especially true in rural counties where a higher percentage of students are Pell eligible. (See "Pell Grants and Community College Success: Improving Metrics via our Community College Survey." Regional Matters, Sept. 8, 2022). There are also many examples of state-funded scholarships, such as the Virginia Guaranteed Assistance Program, the South Carolina Lottery Tuition Assistance Program, or West Virginia PROMISE. Most, if not all, of these state-funded scholarships or grants require the student to be in a for-credit, degree-seeking program. Many also require full-time attendance. One exception to this is the Maryland Community College Promise Scholarship, which was expanded recently to include noncredit programs that lead to industry-recognized licensure or certification.

Typically, federal funding is targeted to the students, via Pell Grants, and not the schools. One notable exception to this was the Higher Education Emergency Relief Funds (HEERF) that were allotted to institutions of higher education in the three COVID-related stimulus bills. This funding represented an unprecedented increase in higher education funds (approximately $4,700 per FTE student). For many schools — particularly community colleges and schools with lower-income students — this was a windfall of funding. For example, Orangeburg-Calhoun Technical College in South Carolina received a total of $14.2 million in HEERF funding — an incredible amount given that its state appropriations in 2022 totaled $5.9 million. This funding, however, is short-lived; HEERF grant performance periods expired on June 30, 2023, with a potential one-year extension for grant spending — through June 2024.

Revenue from local appropriations, largely generated through property or sales taxes, are an important funding source for many community colleges in the Fifth District. Urban community colleges, often supported by growing populations and robust tax bases, are likely to benefit the most from this revenue stream. On the other hand, rural community colleges are more likely to be facing population declines and often are surrounded by other nontaxable properties like state and national parks. For example, Horry Georgetown Technical College, which is located in the same county as Myrtle Beach, S.C., benefits from local appropriations generated by property taxes in Horry and Georgetown counties and sales taxes generated in Horry County. In fiscal year 2022, county appropriations from property taxes amounted to $4.5 million. The technical college also receives 6.7 percent of the revenue generated from Horry County's one-cent sales tax for education, which is a tax largely exported to tourists visiting Myrtle Beach. Between 2008 and 2022, the one-cent tax raised over $953 million, providing Horry-Georgetown Tech with more than $5 million a year in additional funds. Combined, Horry Georgetown Tech gets around $10 million per year from local sources, approximately $1,230 per student. Now contrast that with rural Piedmont Technical College in Greenwood, S.C. In fiscal year 2022, they received $2.7 million in county appropriations, approximately $510 per student.

Enrollment

Even with the addition of federal HEERF dollars and the local appropriations relied upon by some colleges, community college revenue streams rely heavily on funding from state government. And state government funding is tied to enrollment. There are three reasons why understanding the nuance in funding based on enrollment is important. First, there are two ways to think about the number of students in a school: the number of total students taking courses (headcount) and the number of full-time equivalent students (FTEs). For most four-year schools, such as UNC-Chapel Hill, the gap between FTE and headcount enrollment is minimal. At community colleges, however, many more students attend part time. So, while the ratio of FTE to headcount enrollment was 0.91 at UNC-Chapel Hill for the 2020-2021 academic year, that same ratio was 0.51 at rural Sandhills Community College, just 60 miles south.

Most of the time, state and local funding is based on FTEs rather than headcount enrollment. For example, if two students are in school part time, then they are likely considered one student for funding purposes. This makes sense in some cases, such as paying teaching staff or buying machinery. But for most of the services described above, such as career counseling or child care, two students require more resources than one student. And, of course, no funding based on FTEs would include funding for the community-available computer lab.

Second, some community colleges across the district face declining funding due to declines in enrollment. Only in South Carolina — where many community colleges used federal funds to waive tuition for students in qualifying programs for both the 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 academic years — has headcount enrollment increased slightly. (See table.) The funding decrease that will accompany the decline in enrollment could impact the programs that a rural area might rely on from their regional community college.

| Total Headcount (Full- and Part-Time Students) at Community Colleges | |||

| Spring 2019 | Spring 2023 | Change (%) | |

| Maryland | 106,775 | 86,065 | -19.4% |

| North Carolina | 202,800 | 197,468 | -2.6% |

| South Carolina | 72,325 | 74,406 | 2.9% |

| Virginia | 132,893 | 116,280 | -12.5% |

| West Virginia | 11,897 | 9,417 | -20.8% |

| Fifth District Total | 526,690 | 483,636 | |

| SOURCE: National Student Clearinghouse; authors' calculations | |||

Finally, the enrollment (headcount or FTE) numbers include only students enrolled in for-credit programs, with some states providing no appropriations for noncredit programs and some providing FTE funding for noncredit at lower rates than for-credit programs. (The one exception is Maryland, which funds both credit and noncredit programs equivalently.) But noncredit programs (such as programs for commercial driver's licenses) can be critical programs for students at community colleges and the employers they work for, particularly those in rural areas. Since 2021, the Richmond Fed has been working to develop the Fifth District Survey of Community College Outcomes, which will help to better understand the role that noncredit programs play in workforce development. Results of the pilot survey were released in 2022, and the extended pilot survey results will be released in fall 2023.

Where Does the Funding Go?

What do we know about where state appropriations for higher education are being allocated?

Together, Fifth District states spent an annual average of $11.26 billion on higher education between 2019 and 2022. (See chart.) With the exception of South Carolina, which allocates a significant share of its higher education expenditures to direct aid to students in the form of grants and scholarships, the majority of state spending goes toward operational expenses at two- and four-year institutions. Two-year community colleges accounted for an average of 34 percent of public FTE enrollment, ranging from 17 percent in West Virginia to 46 percent in North Carolina. Yet only 27 percent of higher education operational spending in the Fifth District goes to community colleges.

In addition to operating expenses and financial aid for students, states spend between 17 percent and 30 percent of higher education expenditures on functions that are primarily housed at large four-year universities, including research, agriculture stations and cooperative extension programs, and medical school operations.

In all Fifth District states except West Virginia, state funding (for operational and nonoperational expenditures) per FTE is higher for four-year institutions relative to both urban and rural community colleges. The disparity is starkest in Maryland, where four-year institutions receive nearly double the state funding per FTE than rural community colleges in the state. (See chart.)

The gap widens between community colleges and four-year institutions when we look at state revenue per headcount rather than FTE. Funding per student declines for all institutions when counting full- and part-time students the same, but it drops precipitously for urban and rural community colleges. (See chart.)

Many institutions of higher education — from community colleges to large research universities — play an important role in their communities. If the success of economic development is vastly improved by the support and coordination of an anchor institution, and if rural community colleges play that role, then it is important to consider those activities when evaluating the efficacy of funding formulas. The Richmond Fed Survey of Community College Outcomes will provide a better sense of the breadth of programs being offered at community colleges as well as a full accounting of available wraparound services — hopefully providing even more insight into where these institutions fit, and have the potential to fit, in the landscape of workforce, economic, and community development.

Conclusion

Community colleges are publicly oriented institutions that are strongly embedded in their regions; perhaps there is an opportunity to address community needs by aligning resources to provide critical capacity at rural community colleges. To the extent that they play a role in ensuring opportunities and achieving efficient outcomes in rural areas, community colleges may represent an undervalued opportunity.

Subscribe to Econ Focus

Receive an email notification when Econ Focus is posted online.